The Last Person to Turn the Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse Lens by Hand

![]() 5 min read

5 min read

Tucked away on the scenic shores of Jupiter, Florida, the Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse stands as a symbol of the area’s rich maritime history. Its first-order Fresnel lens, an incredible invention from the 1800s, has guided sailors to safety for over a hundred years. Over the Lighthouse’s long-standing service lies a story of resilience and human ingenuity — the story of the last time its Fresnel lens was turned by hand. This pivotal moment was when Charles E. Capps, the last Officer-In-Charge of a separate Jupiter Inlet Light Station, led his team in taking on the task of lighthouse manual operation during a hurricane. This act honored the commitment of lighthouse keepers from the past and the storied history of the Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse.

Guarding the Seas

The Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse, first lit on July 10, 1860, has been a guiding light for mariners navigating the dangerous waters off Florida’s east coast. Its first-order Fresnel lens was manufactured by Henry-Lepaute in Paris. Active since 1866, this lens represents the pinnacle of 1800s lighthouse illumination technology. The lens’s ability to cast light over vast distances has made it an indispensable aid to navigation. However, the Lighthouse’s operation has been challenged, particularly when natural disasters have disrupted its functioning.

Charles E. Capps: A Profile in Dedication

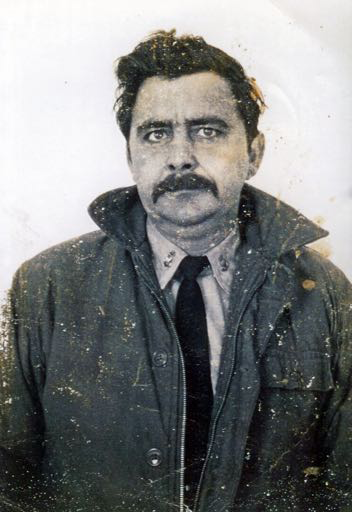

Charles E. Capps, a Chief Boatswain’s Mate (BMC) by his retirement in 1974, had a distinguished Coast Guard career. He spent most of his 21 years of military service at lighthouses and aboard buoy tenders. Capps gained considerable experience in maritime operations before being stationed at the Jupiter Inlet Light Station. His time in Jupiter, from 1964 to 1966, would forever secure his legacy in the history of the Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse.

Charles E. Capps

The Night of the Lighthouse Manual Operation

The day Charles Capps began his duties, October 14, 1964, Hurricane Isbell hit southwest Florida. This storm cut off electricity, putting the Lighthouse and its important light in danger. Not long after the storm hit, the backup generator broke down, threatening to leave the Lighthouse dark. The Lighthouse’s light was crucial for sailors navigating Florida’s east coast.

In the days before automation, the lens rotation mechanism relied on clockwork gears and weights, similar to a grandfather clock, requiring manual winding. When Hurricane Isbell knocked out commercial power, despite being housed in a sturdy concrete building, the backup generator lasted less than 3 hours before failing. This presented Capps and his team with an incredible task.

Remembering the lighthouse manual operation of the past where keepers would manually turn the Fresnel lens, they placed a kerosene lamp at the center of the Fresnel lens. Then began manually rotating the lens to maintain the beacon’s signal —a makeshift solution harking back to the Lighthouse’s earliest days.

For about 90 minutes, under Capps’ leadership, the team ensured that the Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse continued to fulfill its mission of keeping sailors safe from harm. Their willingness to step up and find a way through tough times is a powerful example of true bravery and intelligence in the midst of a crisis.

The Legacy of Manual Operation

The manual turning of the Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse Fresnel lens by Charles Capps and his team represented a temporary revival of practices from a bygone era. Since its electrification in 1928, the Lighthouse had relied on a 1/3 horsepower motor, complemented by a backup motor, to rotate the lens carriage. This modern system replaced the original rotation mechanism. The story of the last manual turning remains a poignant reminder of the pivotal role lighthouse keepers played in ensuring the safety of those at sea.

The Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse stands as a shining example of history and architectural beauty, acting as a guiding light in both a real and symbolic sense. The moment in 1964, when Charles Capps and his crew had to turn the Lighthouse’s light manually, was a short tribute to forgotten times, showcasing their ability to adapt and uphold the traditions of the Lighthouse Keepers that came before them in the face of technological failures.

By 1987, the Lighthouse had fully embraced automation, using a photoelectric cell to control the Light’s bulb and motor, thus ending the era of manual operations and starting a new chapter in the management of lighthouses.

Lindsay Capps Smith, youngest daughter of Charles Capps, recently visited Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse to see where her father once served. Coincidentally, members of CG Station Lake Worth Inlet and CG Base Miami were also visiting the site that day.

Lighthouses' Timeless Role

The tale of the last person to turn the Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse Fresnel lens by hand is more than just a footnote in history. It embodies the essence of dedication, ingenuity, and the enduring human spirit. Charles E. Capps, through his actions during a hurricane, ensured that the Lighthouse continued to serve its purpose, safeguarding mariners against the perils of the sea. As we look back on this moment, we are reminded of the critical role lighthouses and their keepers have played in maritime history and the timeless value of resilience in the face of challenges. This story underscores the continued relevance of lighthouses in today’s digital age, serving as essential beacons of safety, heritage, and unwavering guidance for all who traverse the vast and unpredictable seas.